When Strength Improves but Speed Doesn’t

Rethinking the “Glute Problem” in Sprint Acceleration

Have you ever had this happen?

You work really well with an athlete in the gym.

Strength improves, loads go up, exercises look solid.

Numbers are better, the athlete feels stronger.

Then you go back to the track…

and in the first few steps, almost nothing changes.

Acceleration is still slow, ground contact times remain high, and sooner or later some hamstring tightness starts to appear.

And the obvious thought comes up:

How is this possible? They are clearly stronger.

This scenario is far more common than we like to admit.

And it’s usually at this point that a very natural reflex kicks in:

Maybe they’re still not strong enough.

So we add more load.

More glute work.

More strength.

But what if this is the wrong question?

Is it really a strength problem?

In early acceleration (especially in the first 5–10 meters), performance is rarely limited by force production alone.

Much more often, what actually limits the athlete is:

- direction of force

- timing and coordination

- pelvic control

- the ability to maintain effective positions while the body is inclined

In other words: not how much force the athlete can produce, but how and when that force is expressed.

This concept will be explored in detail in the upcoming webinar.

This is where many coaches — understandably — fall into a strength bias.

We measure strength because it’s measurable.

We track loads, percentages, and progressions.

But we are often much less precise when it comes to evaluating:

- how force is oriented relative to the center of mass

- how well the pelvis is controlled under acceleration

- whether the system allows the glutes to actually contribute at the right time

A common coaching dilemma

Let’s make it concrete.

An athlete struggles to project horizontally in the first few steps.

What do you change first?

Some coaches:

- add more glute strength work

- cue “better positions”

- try to clean up shapes and posture

Sometimes this works.

But sometimes it doesn’t — at all.

Because the real limitation may not be “weak glutes”, but something more subtle:

This concept will be explored in detail in the upcoming webinar.

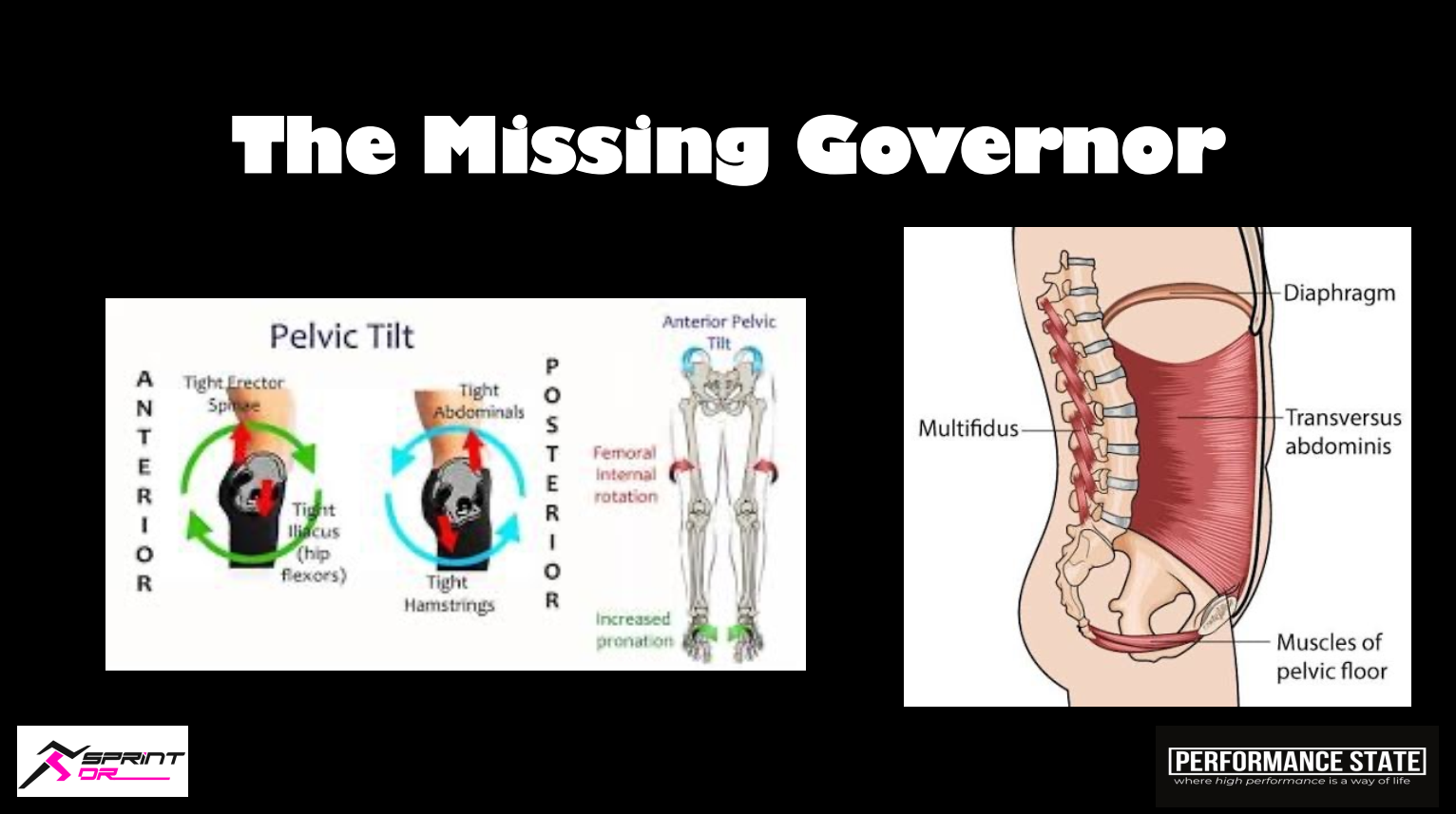

- poor lumbopelvic stability

- insufficient femoral head control

- lack of integration between pelvis, trunk, and lower limb

In these cases, the system simply cannot govern the force that already exists.

And when that happens, strong glutes can still produce:

- foot strike too far ahead of the center of mass

- braking forces instead of propulsive ones

- compensations through the lumbar spine

- early overload of the hamstrings during acceleration

Reframing the glute problem

At this point, the question needs to change.

If the glutes are strong, but force is still braking, what is actually failing in the system?

Often, you can see the answer on the track before touching the gym:

- where the foot contacts relative to the COM

- how the pelvis behaves under forward lean

- how much separation the athlete maintains between thigh and pelvis

- whether positions collapse as speed and intent increase

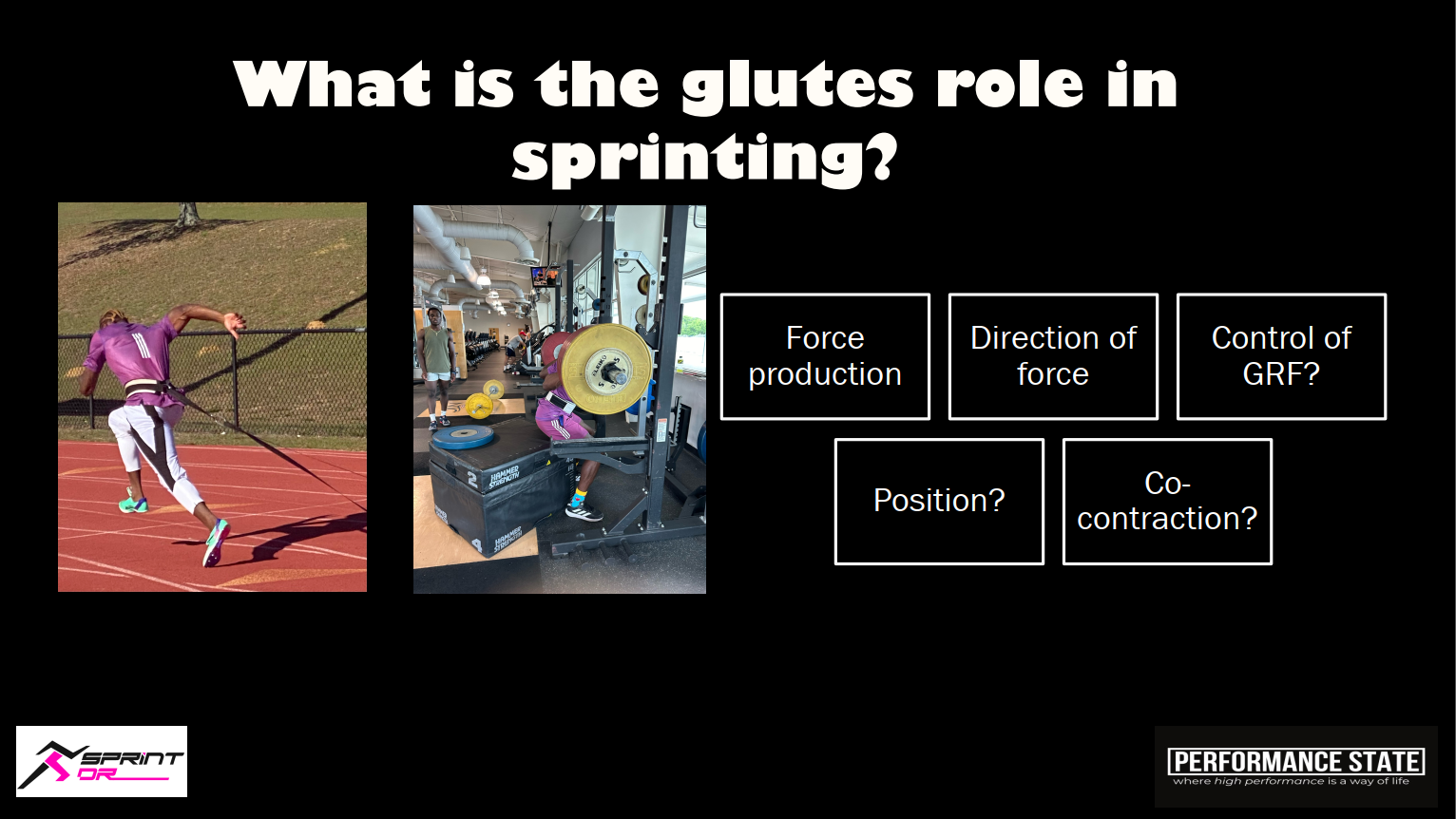

This is where the role of the glutes becomes more complex — and more interesting.

They are not just about force production.

They are involved in:

- force direction

- control of ground reaction forces

- pelvic positioning

- co-contraction and timing

And without the right level of pelvic control and coordination, increasing strength alone rarely transfers to better acceleration.

Access vs strength

This concept will be explored in detail in the upcoming webinar.

One of the most useful distinctions in practice is this:

Strength is not the same as access to strength.

An athlete may be strong in isolated or controlled gym tasks, but unable to:

- stabilize the pelvis dynamically

- coordinate trunk and hip action

- express force in the right direction at the right moment

In these cases, piling on more load can actually worsen the situation, increasing braking and tissue stress instead of improving performance.

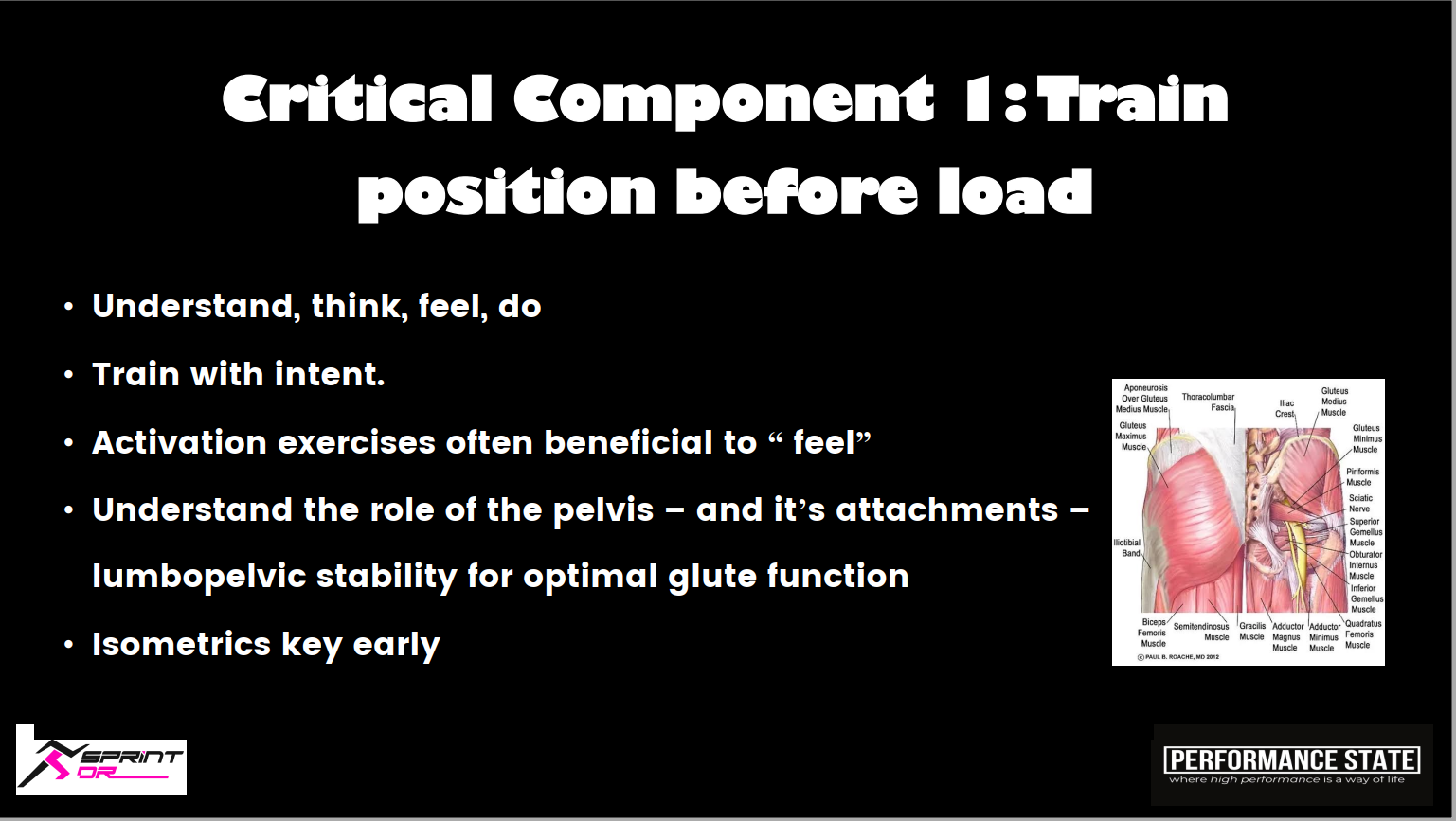

This shifts the training priority.

Before asking how much load, we need to ask:

- can the athlete hold the right position?

- can they control the pelvis under acceleration?

- does the system allow force to flow through the chain efficiently?

Only then does additional strength become meaningful.

One session, one decision

This concept will be explored in detail in the upcoming webinar.

This concept will be explored in detail in the upcoming webinar.

Let’s finish with a real-world scenario.

You have one session this week with a sprinter who shows:

- high ground contact times in early acceleration

- increasing hamstring overload

What do you change first — and why?

This is where system-based thinking matters most.

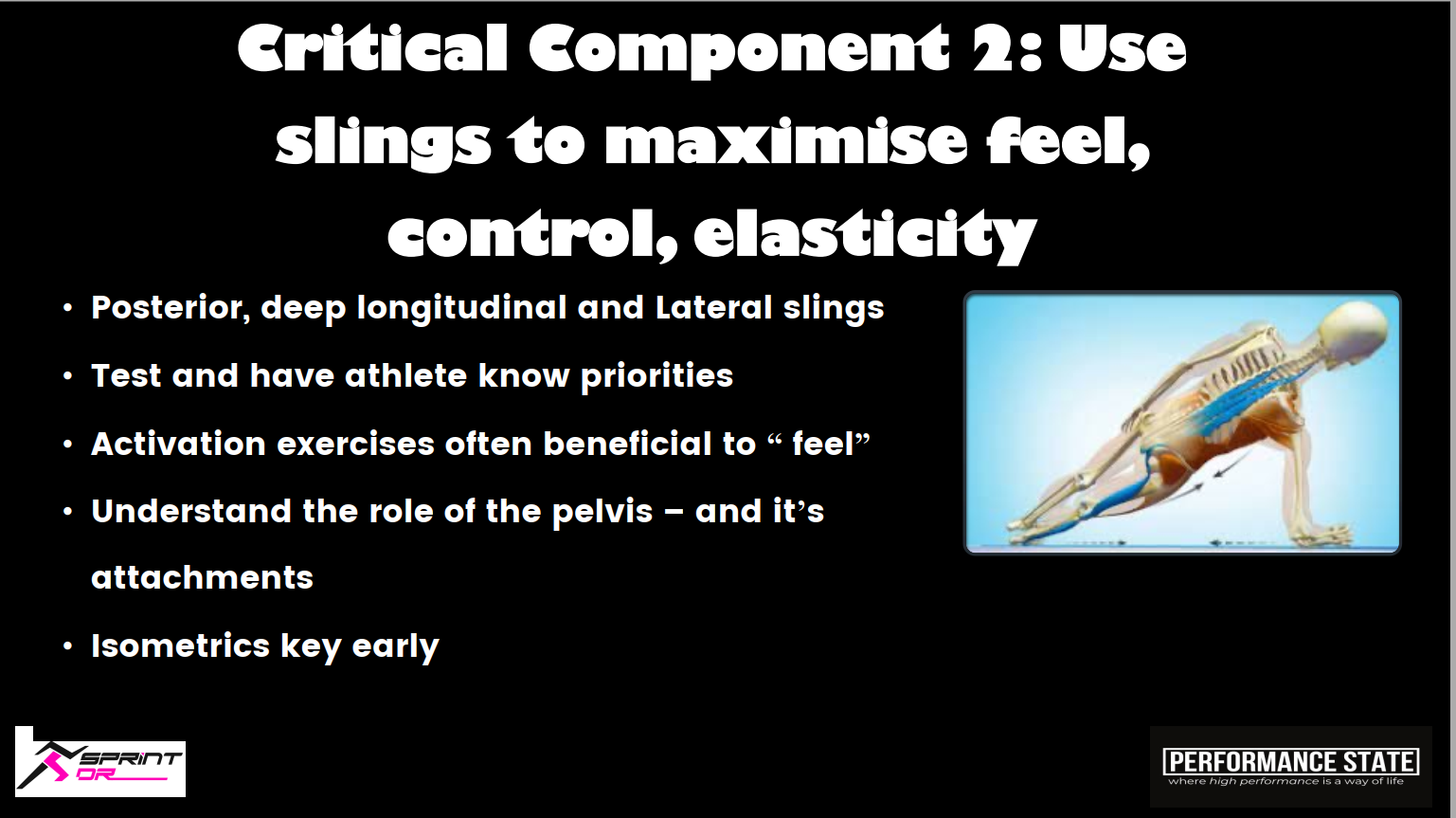

Often, the solution is not adding exercises, but:

- training position before load

- improving lumbopelvic control so the glutes can actually function

- using isometrics and activation not to “fire muscles”, but to improve feel, control, and elasticity

- integrating posterior and lateral slings so gym work transfers to the track

Final thought

The question is no longer:

Are the glutes strong enough?

But rather:

Does the system allow them to do their job?

That distinction alone can change how we coach acceleration.